Researchers create most complete high-res atomic movie of photosynthesis to date

In a major step forward, SLAC’s X-ray laser captures all four stable states of the process that produces the oxygen we breathe, as well as fleeting steps in between. The work opens doors to understanding the past and creating a greener future.

Menlo Park, Calif. — Despite its role in shaping life as we know it, many aspects of photosynthesis remain a mystery. An international collaboration between scientists at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and several other institutions is working to change that. The researchers used SLAC’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser to capture the most complete and highest-resolution picture to date of Photosystem II, a key protein complex in plants, algae and cyanobacteria responsible for splitting water and producing the oxygen we breathe. The results were published in Nature today.

Explosion of life

When Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago, the planet’s landscape was almost nothing like what it is today. Junko Yano, one of the authors of the study and a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab, describes it as “hellish.” Meteors sizzled through a carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere and volcanoes flooded the surface with magmatic seas.

Over the next 2.5 billion years, water vapor accumulating in the air started to rain down and form oceans where the very first life appeared in the form of single-celled organisms. But it wasn’t until one of those specks of life mutated and developed the ability to harness light from the sun and turn it into energy, releasing oxygen molecules from water in the process, that Earth started to evolve into the planet it is today. This process, oxygenic photosynthesis, is considered one of nature’s crown jewels and has remained relatively unchanged in the more than 2 billion years since it emerged.

“This one reaction made us as we are, as the world. Molecule by molecule, the planet was slowly enriched until, about 540 million years ago, it exploded with life,” said co-author Uwe Bergmann, a distinguished staff scientist at SLAC. “When it comes to questions about where we come from, this is one of the biggest.”

A greener future

Photosystem II is the workhorse responsible for using sunlight to break water down into its atomic components, unlocking hydrogen and oxygen. Until recently, it had only been possible to measure pieces of this process at extremely low temperatures. In a previous paper, the researchers used a new method to observe two steps of this water-splitting cycle at the temperature at which it occurs in nature.

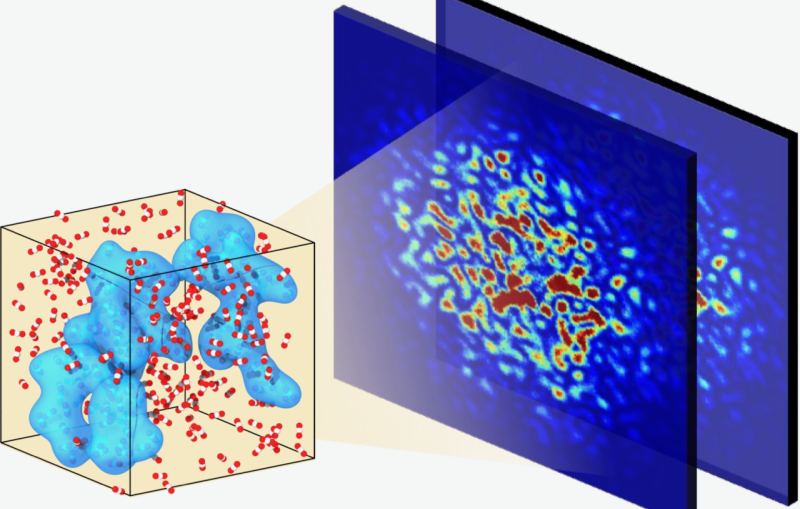

Details of Photosynthesis Captured by SLAC’s X-ray Laser

New X-ray methods at SLAC have captured the first detailed images showing how water is split during photosynthesis at the temperature at which it occurs naturally. The research team took the images using the bright, fast pulses of light at SLAC’s X-ray free-electron laser – the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Chris Smith/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Now the team has imaged all four intermediate states of the process at natural temperature and the finest level of detail yet. They also captured, for the first time, transitional moments between two of the states, giving them a sequence of six images of the process.

The goal of the project, said co-author Jan Kern, a scientist at Berkeley Lab, is to piece together an atomic movie using many frames from the entire process, including the elusive transient state at the end that bonds oxygen atoms from two water molecules to produce oxygen molecules.

“Studying this system gives us an opportunity to see how metals and proteins work together and how light controls such kinds of reactions,” said Vittal Yachandra, one of the authors of the study and a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab who has been working on Photosystem II for more than 35 years. “In addition to opening a window on the past, a better understanding of Photosystem II could unlock the door to a greener future, providing us with inspiration for artificial photosynthetic systems that produce clean and renewable energy from sunlight and water.”

Sample assembly line

For their experiments, the researchers grow what Kern described as a “thick green slush” of cyanobacteria — the same type of ancient organism that first developed the ability to photosynthesize — in a large vat that is constantly illuminated. They then harvest the cells for their samples.

At LCLS, the samples are zapped with ultrafast pulses of X-rays to collect both X-ray crystallography and spectroscopy data to map how electrons flow in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. In crystallography, researchers use the way a crystal sample scatters X-rays to map its structure; in spectroscopy, they excite the atoms in a material to uncover information about its chemistry. This approach, combined with a new assembly-line sample transportation system, allowed the researchers to narrow down the proposed mechanisms put forward by the research community over the years.

Mapping the process

Previously, the researchers were able to determine the room-temperature structure of two of the states at a resolution of 2.25 angstroms; one angstrom is about the diameter of a hydrogen atom. This allowed them to see the position of the heavy metal atoms, but left some questions about the exact positions of the lighter atoms, like oxygen. In this paper, they were able to improve the resolution even further, to 2 angstroms, which enabled them to start seeing the position of lighter atoms more clearly, as well as draw a more detailed map of the chemical structure of the metal catalytic center in the complex where water is split.

This center, called the oxygen-evolving complex, is a cluster of four manganese atoms and one calcium atom bridged with oxygen atoms. It cycles through the four stable oxidation states, S0-S3, when exposed to sunlight. On a baseball field, S0 would be the start of the game when a player on home base is ready to go to bat. S1-S3 would be players on first, second, and third. Every time a batter connects with a ball, or the complex absorbs a photon of sunlight, the player on the field advances one base. When the fourth ball is hit, the player slides into home, scoring a run or, in the case of Photosystem II, releasing breathable oxygen.

The researchers were able to snap action shots of how the structure of the complex transformed at every base, which would not have been possible without their technique. A second set of data allowed them to map the exact position of the system in each image, confirming that they had in fact imaged the states they were aiming for.

Sliding into home

But there are many other things going on throughout this process, as well as moments between states when the player is making a break for the next base, that are a bit harder to catch. One of the most significant aspects of this paper, Yano said, is that they were able to image two moments in between S2 and S3. In upcoming experiments, the researchers hope to use the same technique to image more of these in-between states, including the mad dash for home — the transient state, or S4, where two atoms of oxygen bond together — providing information about the chemistry of the reaction that is vital to mimicking this process in artificial systems.

“The entire cycle takes nearly two milliseconds to complete,” Kern said. “Our dream is to capture 50-microsecond steps throughout the full cycle, each of them with the highest resolution possible, to create this atomic movie of the entire process.”

Although they still have a way to go, the researchers said that these results provide a path forward, both in unveiling the mysteries of how photosynthesis works and in offering a blueprint for artificial sources of renewable energy.

“It’s been a learning process,” said SLAC scientist and co-author Roberto Alonso-Mori. “Over the last seven years we’ve worked with our collaborators to reinvent key aspects of our techniques. We’ve been slowly chipping away at this question and these results are a big step forward.”

In addition to SLAC and Berkeley Lab, the collaboration includes researchers from Umeå University, Uppsala University, Humboldt University of Berlin, the University of California, Berkeley, the University of California, San Francisco and the Diamond Light Source.

Key components of this work were carried out at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS) and Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source (APS). LCLS, SSRL, APS, and ALS are DOE Office of Science user facilities. This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science and the National Institutes of Health, among other funding agencies.

-Written by Ali Sundermier

Citation: Kern et al., Nature, 7 November 2018 (10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2)

Press Office Contact: Manuel Gnida, mgnida@slac.stanford.edu, 415-308-7832

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.